Background

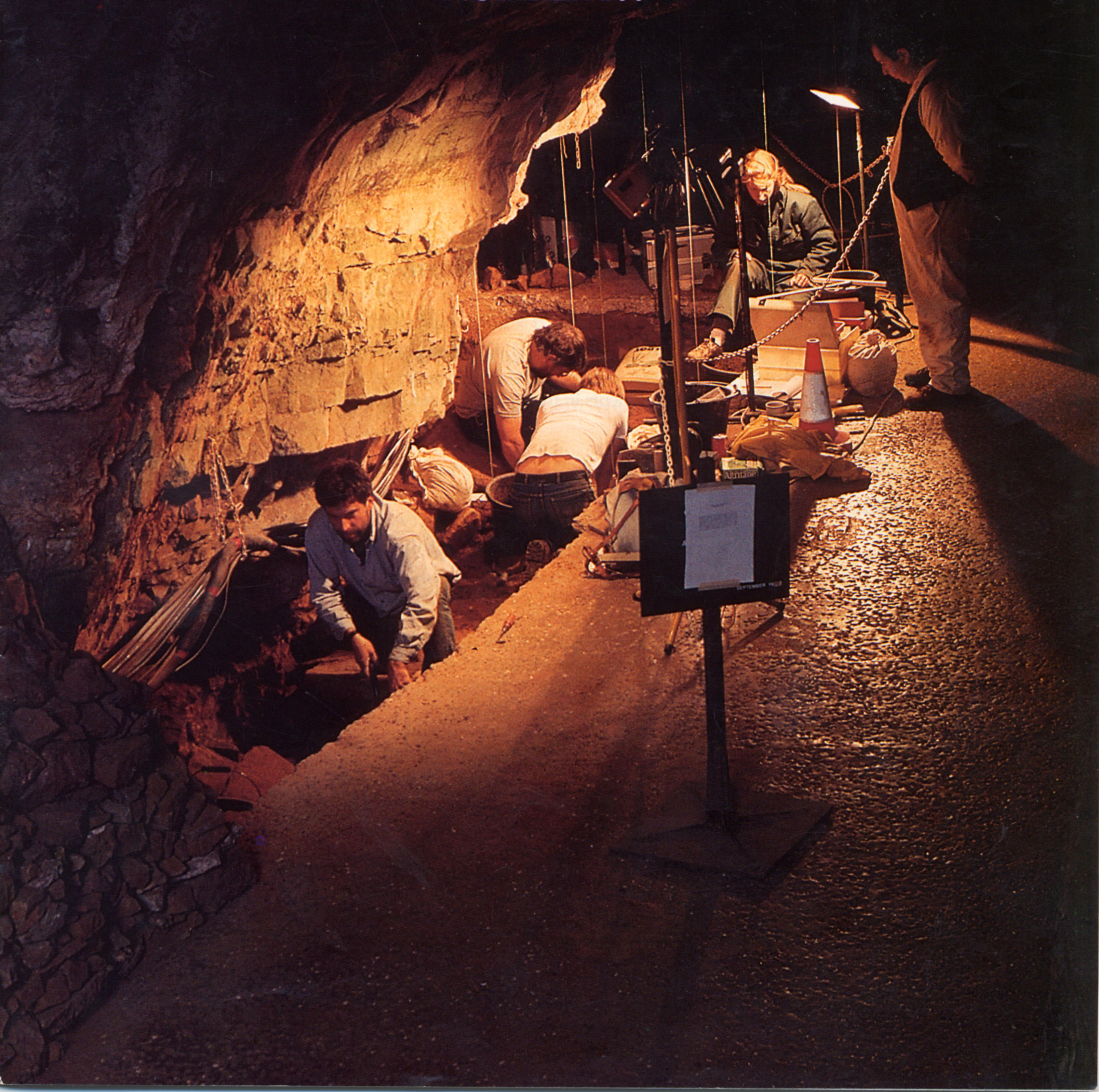

Gough’s Cave is Britain’s most significant later Upper Palaeolithic site with the largest collection of human remains from the British Pleistocene as well as one of the most diverse set of mammalian remains from the Late Glacial. A show cave located in Cheddar Gorge in the Mendip Hills, Gough’s was first excavated by Richard Gough in the last decade of the 19th Century. The cave has yielded one of the largest collections of artefacts and faunal remains of any Upper Palaeolithic cave in Britain. Recent excavations in the 1980s uncovered new material and improved understanding of the cave’s stratigraphy. Most of the fauna comes from a clastic wedge that filled the entrance, most of which dates from about 14,700 years bp. The site appears to have been associated with horse hunting and its fauna was accumulated by people, most of the bones having cut marks and associations with human-worked artefacts. Human remains at the site show signs of contemporary post-mortem processing that suggest Upper Palaeolithic cannibalism.

Chronology

Careful study and radiometric dating of the human-marked faunal remains have provided important evidence for the chronology of Late Glacial human reoccupation of northwest Europe. Reanalysis of stratigraphy and dates suggest that the cave was occupied for only a short period, perhaps no more than two or three human generations. This occupation began no earlier than 14,840 to 14,680 calendar years before present and the oldest direct evidence for human occupation is 12,600 radiocarbon years before present (14,950 to 14,750 calendar years). The recolonization of Britain seems to have taken place at the same time as the rapid warming associated with the beginning of Greenland Interstadial 1 (Bølling Interstadial).

Human fossils

The most thought-provoking finds from Gough’s Cave are the associated human bones. They represent a minimum of five individuals – a young child, who died at around three years of age, two adolescents and two adults. These bones and teeth show no sign of disease or developmental stress during growth, but numerous cut marks, scratches and breaks litter their surfaces. The fragmentary limb bones had been deliberately smashed and ribcages opened up, with cut marks particularly concentrated on the skull bones. These individuals had apparently been defleshed after death, and this appears to be evidence for nutritional cannibalism during the late Upper Palaeolithic. Experimental work has confirmed that at least some of the bones show marks made by human teeth rather than those of other carnivores, so people were chewing the toe and rib bones of their contemporaries. Other clues corroborate this. The mandibles of humans and animals had both been severed from the head before being defleshed and deliberately broken, presumably a butchery practice designed to extract as much edible soft tissue as possible. There was also no discernible difference in terms of where and how remains had been discarded – human and animal bones were jumbled up together, apparently dumped in the same place.

The most persuasive evidence for more complex (ritual?) behaviour is the meticulous post-mortem decapitation and treatment of the head. Cut marks on the neck vertebrae and at the base of the skull show that the head was removed before decomposition (which would have led to its natural disarticulation), and thus probably shortly after death. The front teeth on two upper jaws (maxillae) bear fractures and scratches, consistent with the lower jaws (mandibles) being prised free from the rest of the skull with the aid of a lever placed in the mouth. Further cut marks show that the major muscles on the sides of the skull were then removed, along with the lips, tongue, ears and nose. Others around the eye sockets suggest removal of the eyes, and a great number of cut marks around the cranium point to scalping. In three cases, with soft tissue stripped, the base of the skull and face were then carefully struck off, and the edges shaped via secondary trimming with a hammerstone and anvil. The occupants of Gough’s Cave apparently aimed to carefully preserve the braincase, isolating and cleaning the cranial vault scrupulously with stone tools, before shaping it with precision. The skulls were not simply bones from which flesh and marrow was extracted for food, but instead they were carefully preserved in order to transform them into ‘bowls’. Similar modification has been recorded at two French sites of comparable Magdalenian age: Le Placard in Charente, and Isturitz in the foothills of the Pyrenees, where some skull-cups even bore engraved representations of animals.

|